Introduction

Between May 2023 and March 2025, Tract attempted to build a venture-backed company to address Britain’s housing crisis by improving the planning permission process. After raising a £744,000 pre-seed round in April 2024, we explored several business models: a site-sourcing tool for developers (Tract Source), a free land-appraisal tool for landowners (Attract), becoming tech-enabled land promoters ourselves, and finally, an AI-powered platform to assist with drafting planning documents (Tract Editor).

Despite significant technical progress, building tools like Scout and the well-received Tract Editor, our journey taught us critical lessons from failing to secure a viable, venture-scale business model in the British property market. We learned the difficulty of selling software into a conservative sector, experienced the operational complexities and timelines of land promotion, and encountered a low willingness to pay for useful tools. Furthermore, we came to understand how the market's conservatism and fragmentation limited its potential for venture-backed disruption. After nearly two years without revenue or committed paying customers, we realised we lacked a clear path to the necessary scale and returns. This prompted the decision to cease operations and return capital, sharing our experience as a case study.

In retrospect, it's easy to see ways we could have approached things differently. This document is a post mortem, explaining what happened and why it went wrong. Our aim in writing this is:

- Codify and share what we’ve learned for our benefit and hopefully others.

- Document the story for posterity.

- Produce an artifact to explain, if not justify, the time and money spent.

- Exorcise our demons.

We want to stress from the start that the ultimate failure of the company lies with us. Some issues were within our control and some were beyond it. At times, we’ll describe external factors in ways that sound negative. This isn’t an attempt to pass blame. We want to tell the story as matter-of-factly as possible. Most importantly, we’re extremely grateful to everyone who supported us over the last couple of years, in money and in time.

Jamie Rumbelow

and

Henry Dashwood

April 2025, London

Table of Contents

This document is long; this table of contents also functions as a bullet-point summary. The Advice for Founders section contains the main lessons we hope people take from our experience, so feel free to only read that and skip the rest.

You can also

summarise this page with ChatGPT.

Introduction jump to

- In May 2023, Tract was founded to build software to fix Britain’s housing crisis.

- We raised a £744,000 pre-seed round in April 2024.

- We decided to wrap up operations and return capital to investors in March 2025.

Mission and worldview jump to

- Housing in Britain is expensive because getting planning permission is difficult.

- Granting permission takes the median hectare of land from £20,000 to £2.4 million - a 139x uplift.

- If we can reduce the costs and uncertainty of this process by any reasonable amount, we can build a business and help solve the housing crisis.

Reflections jump to

Things we did well: jump to

- Raised capital for an unusual business in a difficult market.

- Built good technology and solid products.

- Pivoted quickly in December when we realised our strategy wasn’t working.

- Learned a lot about a complex industry quickly.

Reasonable errors: jump to

- Overestimated British market size and receptiveness.

- Raised venture capital for a model that probably should have been funded differently.

- Focussed too much on technology over business development.

- Built out the team too early.

- Didn’t consult land agents early enough.

- Failed to capitalise on Scout’s success.

- Spend lots of time and money on non-essentials.

- Didn’t focus on getting to revenue.

Advice for founders: jump to

- Get to the US - larger, higher-quality market, better ecosystem for building companies.

- Focus on market quality - receptive customers, clear decision-makers, fast learning cycles.

- Stay lean until you have proven revenue.

- Be aggressively commercial from day one.

- Test hypotheses quickly and thoroughly.

- Always ask yourself, “what have I learned from customers?”

What's Next? jump to

- Jamie is interested in new projects. Email him.

- Henry is also interested in new projects. Check out his website.

Appendices jump to

- Further reading

- Things that should exist

- Things that already exist

The Mission

Many young people have had to delay forming families and often take poorly paid, insecure jobs that can barely cover rent and living costs as the price for living in culturally attractive cities. They see opportunity as limited and growth as barely perceptible. Meanwhile, older generations sit on housing property worth many times what they paid and, stuck in a zero-sum mindset, often prioritise the protection of their own neighbourhoods over the need to build more homes. Can you blame young people who resent older people, and the West’s economic system itself, when this is what it offers them?

Myers, Bowman and Southwood, The Housing Theory of Everything

Housing in Britain is expensive because of artificial supply constraints - specifically, the difficulty of obtaining planning permission to build more. Planning permission is Britain’s regulatory approval that landowners must secure before developing land or changing a building's use. When permission is granted to build homes on agricultural land, its value increases dramatically (often 140x or more), creating enormous wealth for landowners.

This looked like a business opportunity: if we could help more sites get planning permission, we could capture some of that uplift. The market size looked compelling - billions in Britain alone, the political winds seemed favourable, and there seemed to be few modern software solutions.

We were driven by a mix of moral outrage and technological optimism. It seemed absurd that bureaucratic obstacles were holding back so much potential value, especially when millions were being spent on documentation that could be automated. With the rise of LLMs, we believed we could transform this inefficient process.

Timeline

Tract Source (May 2023 - October 2023)

Strategic land teams are groups within property development companies responsible for identifying and acquiring land with long-term development potential. They focus on finding sites that don’t yet have permission for development but possess characteristics that suggest it could be obtained in the future. The earlier they can identify and secure control of these sites, the greater their competitive advantage and profit potential.

This felt like a software-shaped problem and could form the basis of a larger platform for planning, moving elsewhere along the value chain. When Jamie began working on Tract, this site sourcing problem was the first thing he looked at.

Some sourcing tools existed, but the popular options seemed poorly built: badly designed, built atop untrustworthy data sources, and not built around the sourcing workflow.

Jamie had ideas to improve the product experience and began building them out. He started to lean on industry advisors for introductions. He read The Mom Test (more on which later) and had dozens of calls with whoever would take them.

During these calls, he realised his intuitions about the existing products’ problems were correct (“I don’t trust it”, “I need to check the numbers, it’s annoying”). This was exciting: he thought he was onto something.

But he didn’t ask why users tolerated it (“It’s fine”, “Does what I need”, “We went with [competitor] because, to be honest, they’re nice guys”). It was unlikely whatever he built could be 10-100x better at solving this problem without radically changing their workflow, which was tough for a solo developer working on savings – Henry began helping in his free time from late summer but wouldn’t come on full time until mid-December.

Jamie also began to find more competitors, some well-resourced, all of whom appeared to be competing on price. These were already cheap contracts: a few hundred pounds per month for a small/medium-sized team. And they were getting cheaper.

We concluded that this was a difficult market to sell into, with race-to-the-bottom pricing dynamics, and no obvious way to make a SaaS tool that helped strategic land teams do site selection so well that these factors wouldn’t matter. It was time to pivot.

Learnings

This process gave us:

- a better understanding of the problem space and competitive environment;

- the basis of a network;

- and time in which the early data infrastructure which would support our subsequent products was built.

However, it took too long to reach the pivot point. A more thorough competitor analysis would have revealed the market problems earlier, rather than being distracted by writing code. None of what we needed to learn required writing code to get there.

The biggest lesson here: getting time-to-validation as low as possible matters more than anything else. If there are ways faster to get there, you should take them.

Interlude: Attract (October 2023 - November 2023)

Our site appraisal tool, Attract, emerged from discussions with our design partner Paul and from Tract Source's challenges. The concept was simple but promising: instead of selling land information to developers, we’d provide it to landowners for free. The greatest constraint for any promoter or developer is access to developable land, so we imagined a tool encouraging landowners to reveal their openness to development would be valuable. The generated appraisals would allow us to rapidly qualify sites and identify potential opportunities.

Initially, we considered selling this tool to developers and land promoters seeking strategic land opportunities. However, we quickly recognised two fatal flaws in this approach:

- The economics didn't work—we couldn't charge more than £50/month/customer, and there weren’t many customers.

- We'd face the same sales challenges as Tract Source, compounded by the fact that this was an unconventional solution with no market precedents.

Despite this, Jamie completed the conversion work and launched a white-labelled version on Paul’s company’s website in early November. It delivered impressive results: he received more submissions and higher-quality leads. This quick win validated our technical approach, but the underlying business model remained insufficient to build our company.

This experience taught us something valuable: we could create genuinely useful tools that solved real problems. However, we still hadn't cracked how to transform that utility into a venture-scale business model.

November 2023 - January 2024

With the white-labelled version of Attract online, we entered a period of exploration and uncertainty. We had a call with a major surveyor where we showed them a mocked-up tool for writing a planning application using an LLM and the information about a site in our database. But after the demo, we were ghosted.

Market concerns loomed large. The pricing dynamics made us question our ability to raise capital with our current approach. In retrospect, we may have been closer to viable products than we realised. Multiple British prop-tech companies have been funded, including in the US, during the lifetime, suggesting alternative paths we could have taken.

Despite challenges, we continued experimenting. In December, we created a ‘Tinder for Buildings’ demo with inpainting models that received positive feedback. We continued scoping ways to build a business on our planning data work. We were awarded an Emergent Ventures grant, validating our mission if not our approach.

JRAt this stage, we were clearly concerned about the market, but I don’t think we did enough – now or indeed later – to precisify those concerns. We gave up on the platform idea because of a couple of crappy meetings, rather than work out how to pitch better. It feels like we weren’t trying hard enough to be an organisation that learned from its mistakes.

January 2024 - May 2024

In January, we began fundraising while working on extracting Local Planning Authority validation checklists—technical work to support our evolving vision.

A February visit to a developer proved illuminating, though not as hoped. Their skeptical in-house planner admitted: "To be honest, the system being broken helps us." This comment crystallised a tension in our market: many established players benefited from the inefficiencies we aimed to solve.

This realisation prompted us to revisit our fundamental problem statement. The facts were compelling: land with planning permission becomes dramatically more valuable, and this value creation stems from the friction and uncertainty in the planning process—friction that good software could reduce.

We faced a dilemma. Selling software into this market would be tough, and it seemed wasteful to capture only a small slice of the value we could create. If we could facilitate 100x value increases in land, why sell this capability to others for modest SaaS fees? What B2B model could compete with capturing that uplift directly?

We considered a radical pivot: becoming land promoters ourselves. We’d partner with landowners or acquire land, secure planning permission using our technology, and sell with permission granted—capturing the value uplift directly.

We found another opportunity: promotion costs don't scale linearly with site size, making many smaller sites economically unviable for traditional promoters. We could counterposition by targeting these ignored sites and sell them to SME developers.

This model offered significant advantages:

- We avoided selling software to a resistant market.

- The potential revenue and profit margins were substantial, especially if we could reduce costs through automation.

- We had a clear technological roadmap: automate the existing site selection and planning application processes.

- As our own customer, we could optimise an industry that underutilised modern technology.

Implementation would be challenging—some aspects like site visits couldn't be fully automated—but we believed we could create a durable advantage by controlling the critical fulcrum point where planning permission is granted.

This became our fundraising narrative:

(click to view full deck)

During the fundraising process however, we identified a bottleneck: access to land. Without reliable land access, our growth would be constrained. How would we:

- put ourselves in front of landowners,

- identify the ones open to selling,

- get them over the line?

One investor – who ultimately passed – described this challenge as requiring extensive "hand-cranking"—an apt analogy. But at the time, we thought Attract could solve our top of funnel problem.

Rather than white-labelling the tool for strategic land teams, we could own it, market aggressively to landowners, keep the sites we want to develop ourselves and pass the rest to strategic land teams for a referral fee. Appraising land and advising on its development potential is part of what a land agent does. We would be automating that.

Why would a landowner use our tool? Partly out of curiosity like taking personality quizzes, but also because our information was genuinely useful. Land agents bill hundreds of pounds for appraisals with the same information we could pull programmatically. Henry had recently commissioned two appraisals for sites following advice his family had received. They were £600 each and contained:

- A summary of planning constraints for the site (e.g. conservation areas, nearby listed buildings, where the village sat in the settlement hierarchy).

- Relevant local plan policies (e.g. what development to encourage/discourage).

- Previous planning applications for the site.

We already had this information or plans to collect it. We could generate these appraisals, give them to landowners for free, and use this to solve the top-of-the-funnel problem.

We made a subtle but critical error here - we assumed the problem was limited to the top of our funnel (identifying landowners and sites). In reality, as we'd discover, no part of the funnel was robust enough to build a venture-scale business in our required timeframe.

Had we recognised this earlier, we might have concluded this business lacked venture-scale potential, or we could have examined how to modify our approach.

JRWe could have done more with this insight if we had been more operationally effective. We could have done our own site-search process, generated appraisals for sites we liked, printed them out, and mailed them to the landowners. (This wouldn’t have solved the venture-scale problem, but I’m not sure we gave this horse enough of a flogging before calling it dead.)

Learnings

We still agree with the principle behind this pivot; that the next generation of billion-dollar companies may sell work, not just software, and that this is especially true in UK proptech. We’re happy with the reasoning. But we were entering an industry to do something we had no experience in, and without any commercial traction.

Paul Graham has an essay where he says the most efficient question to ask founders is “What have you learnt from users?”. One problem this question would have exposed if we’d asked it was that we hadn’t spoken to the people using Attract and who would develop their land with us. The people we were speaking to and learning about planning and development from weren’t our actual users. This meant we couldn’t begin testing our product’s commercial traction by asking if a user would pay for it.

Although we erred by not getting relevant user feedback while we had months of savings, the focus in the latter part of the raise to build a business plan was probably correct. We were working on Tract unpaid. As the deadline to raise money approached, our focus was (not unreasonably) on getting the funding to survive.

These weeks were a success: we raised capital in a tough situation when the alternative was to shut down and get jobs. However, we had backed ourselves into a corner, not taking advantage of the previous time to run a rigorous market and product-discovery process.

HDIf I were to start a startup again, I’d take more time and be more intentional in talking to potential customers before needing to raise money. Ironically this feels easier having been through the process once. I’m more comfortable reaching out, focusing my questions to avoid wasting time, and moving the conversation towards getting a firm but useful “No.”

JR+1; especially annoying given how much Mom Test I had read by this point. Something that this section demonstrates well, I think, is how much we were flailing. We never really regained our focus after this point.

HDI’d be more aggressive about finding a narrow marketable product. “Ship an MVP” isn’t a novel insight, but post-fundraise, we were too complacent.

The Fundraise (January 2024 - April 2024)

Since raising capital, we've learned our fundraising experience was unusual. VCs operate with a fundamental asymmetry: it costs them virtually nothing to stay in touch with a company without investing, but missing the next unicorn can be catastrophic to their portfolio returns. This creates a dynamic where they'll meet hundreds of companies annually, rarely delivering outright rejections.

Contrary to the "VCs never say no" stereotype, most were capable of clear passes: "not a market we know enough about" or "we're not convinced about this aspect of the pitch." The key insight is this: if a VC sees potential, they move quickly. If you're stuck in a holding pattern of positive but non-committal feedback, their current position is likely "no"—they're leaving the door open in case you gain traction or pivot to something more compelling.

We found ourselves in this holding pattern. One VC was interested but nervous about leading the round, while at another, the lead partner wanted to write an angel check but wouldn't commit to funding institutionally. This created a frustrating cycle of meetings yielding positive feedback followed by requests for "just one more" spreadsheet or one-pager to clarify something. During this period, we worked to integrate early Attract usage data into our narrative about targeting small sites as land promoters.

Through delicate back-channeling between the two firms, we got them as joint leads, with five angels joining the round. We then experienced that classic founder moment where, after securing a term sheet, several other firms expressed interest.

The process from term sheet to closing took over a month. Despite being a straightforward priced round, we had to pay both teams lawyers to negotiate minor details. In San Francisco, a deal this size would have been done with a quick SAFE note, so it was frustrating to spend £25,000 out of the £744,000 we raised on legal fees.

Learnings

Warm intros are 100x better than cold outreach - maybe one or two VCs set up calls from a cold email, out of ~50, whereas nearly every warm intro was happy to talk to us. These came from former colleagues who became investors or had startups and introduced us to their VCs. People want to make and receive introductions. So, assuming you make a good impression, feel free to ask for help. If they don’t feel comfortable (maybe they don’t they don’t feel comfortable (maybe they don’t know the person well, or they’ve recently taken up a lot of their time, or they’re busy) they will politely explain why.

Running a well-organised raise is better than not, but you can’t really plan it. Unless you have hockey-stick growth and a surplus of investor interest, you need to work whichever angle you have, even if it means abandoning your existing plans.

Try to raise early rounds on a SAFE/ASA - even in tranches, even if it means accepting less cash or a lower valuation, even if it complicates your cap table. Despite capping legal fees at each stage, we spent £25,000 on lawyers – capital that should have gone toward building our business. We waited over a month for the money and were distracted figuring out legal terms.

Not every business suits VC - If you’re interested in technology or startups, you’ll hear lots from venture capitalists. This is partly because they engage in content marketing and thought leadership to attract dealflow and partly because being a VC requires optimism and interest in the future. So their interests will overlap with yours as a startup founder. But before you raise money from them, consider if your business fits their financing model. Venture investments follow a power law model. Venture investments follow a power law where a few pay off so well that they cover the others that go to ~zero.

A good pitch to a VC should acknowledge the risks of the company failing, but not eliminate them. The focus should be on the huge opportunity if you overcome them. For decades, software companies fit this model. There’s a risky startup stage,but if a company survives, they can build moats through network effects (the most useful platform is the most popular) and switching costs (migrating data and workflows to a new system is hard).

Not every business is like this. In real estate, you may have a thesis about where demand is going. You may make speculative acquisitions or invest in site improvements before selling. It’s unlikely these bets will pay off 100 to 1000x like the best venture investments. However, a good thesis and execution can generate an internal rate of return of 10 to 20% - more than keeping pace with a VC fund’s aggregate return. There are investors interested in these opportunities but they make less noise than VCs. They are often family offices, and may be the LPs of venture funds.

Some companies try to balance being a high-risk bet with high per deal costs by raising money from VCs for an operating company and property investors for a property company. The former bet on the company growing to process many deals,while the latter bet on the success rate of those deals. These complex deals require careful alignment of everyone’s incentives.

If these last paragraphs resonate, check out Brad Hargreaves or Nick Huber’s writing. See the further resources section for useful posts from Brad’s Substack for anyone considering financing options.

April to November 2024

Marketing to landowners proved difficult. An appraisal tool for farmers doesn't go viral. We identified things like niche Google searches e.g. specific DEFRA forms with low ad competition, but a few thousand pounds of ad spend generated minimal activity.

The challenge: landowners might pay hundreds for an appraisal, but rarely need one. Identifying and reaching them at their moment of need was nearly impossible.

We made two critical mistakes:

- We spent three months rebuilding the Appraisal tool before contacting landowners who had submitted sites through our MVP. These existing submissions represented our only real users, yet we failed to nurture these relationships or learn from them immediately. We didn't take them seriously enough as potential customers.

- Second, we failed to understand the basic economics of land agency—the business we were trying to replace. When we spoke with established land agents, we discovered uncomfortable truths: they completed very few referrals, and each took 18-24 months minimum to process.

JRThese errors seem SO STUPID in hindsight. Such an own-goal. So easy to avoid. And something that everybody talks about, all the time. Don’t overbuild; invalidate your assumptions.

Land agents are fragmented: many serve small geographic areas. A birds-eye view of this market suggests you can roll it up for economies of scale. We liked this logic, so we pursued it.

We didn’t consider if the fragmentation was a feature rather than a bug. Each agent spends a lot of time building the social infrastructure – going to fairs, drinking in pubs, befriending the parish council – needed for these deals. Landowners are a small-c conservative customer, and they don’t respond well to audacious pitches and fast timetables. These deals take 18-24 months because these are emotional decisions, not scalable ones.

Two or three phone calls could have revealed this reality and neutered any delusions about revolutionising this industry. Instead, we wasted six months—three building software and three wondering why nobody used it.

Compounding these errors, we hired extra marketing and operations staff based on flawed assumptions:

- We had no evidence that more marketing would help without a proven customer acquisition strategy;

- We weren't constrained enough to justify these hires—we should have pushed ourselves harder first.

We found a few promising sites where the landowner was eager to collaborate. However, further investigation revealed unique complications that would require bespoke work taking months to resolve before we even got onto the steps we aspired to automate. This wasn’t a deal breaker, but it would mean using nearly all our capital to bet on four sites over the next couple of years. If we got them through the system, we could make enough money to repeat the process at a greater scale. However, it was also possible that we wouldn’t. We would have spent two years working as conventional land promoters, which others could do better.

As we considered the sites we had and ways to increase submissions, we explored higher leverage ways to use our skills. What was our comparative advantage? We could build software. So we dove back into the murky world of pure proptech.

Interlude: The Grid (December 2024)

The state of our electricity grid is an important story. Whenever we met a developer, residential, commercial, or energy, the uncertainty about how long they would be stuck in the interconnection queue and how much they might pay in first or second comer charges would come up. Delays or unexpected charges could run into the millions.

We lack good tools for modelling the grid. At the time of writing the National Energy System Operator’s map thinks that Didcot is on the Isle of Wight, and Sizewell B is in Scotland. If you want to build something that will draw from or inject significant power into the grid, you need to know:

- What is the current capacity around your proposed site?

- What will the capacity be in the next few years?

We already had a map with layers like power line and substation locations, voltages, and official headroom capacity.

DNOs publish their actual headroom monthly in tables called the embedded capacity register. It wouldn’t be hard to add that.

We were scraping planning applications to build a model of future generation and demand growth.

At the year’s end, we explored whether this was a worthwhile pivot opportunity. We found a couple of developers who hired consultancies to build internal tools at great expense. We found a couple of start-ups whose demos didn’t justify the huge prices for features on our roadmap. We had exciting conversations with one energy developer about a design partnership. They wanted a platform to find companies in the connection queue open to selling their spot.

Our idea was speculative, requiring us to negotiate deals in an unfamiliar industry. Meanwhile, we were making progress with the Editor project. So we shelved this idea.

HDI still think someone could build a trading platform for this, not just for trading queue spots, but for pooling resources to fund infrastructure upgrades to unlock multiple projects.

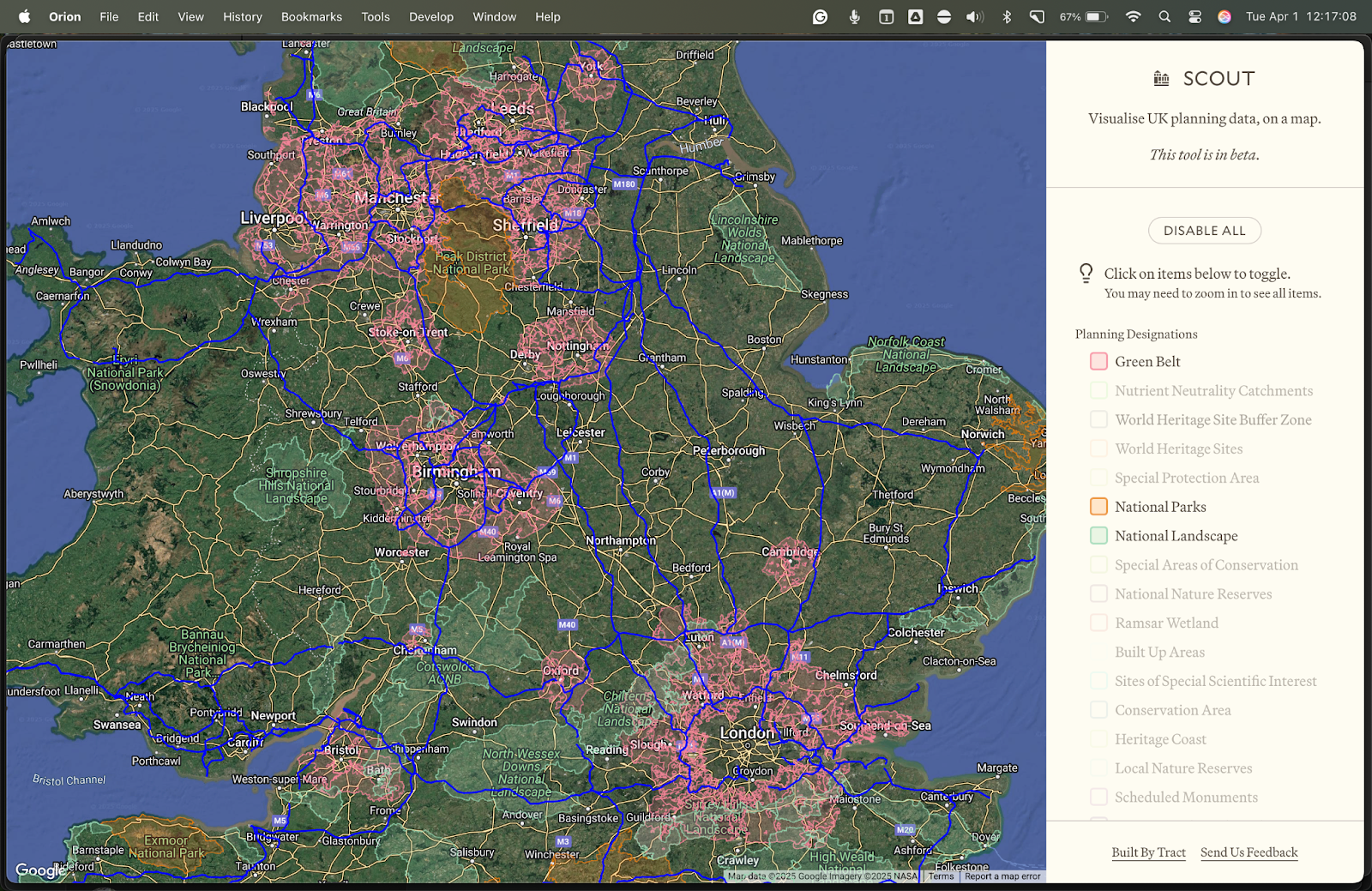

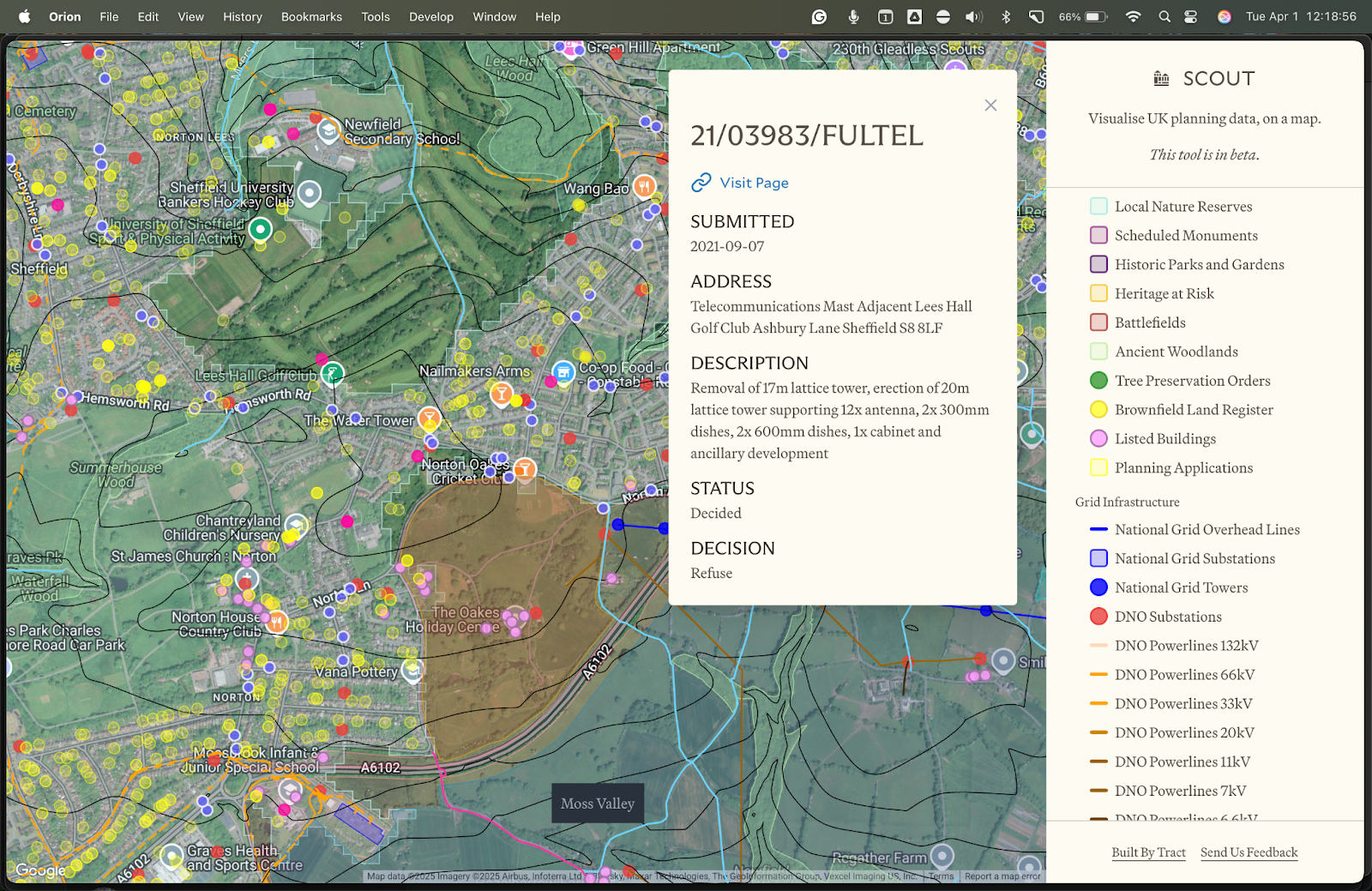

Interlude: Scout (December 2024)

While attempting to build a land promoter, we started using Landstack, a site sourcing tool, with good quality datasets that we hadn’t ingested. We had no desire to compete with them or steal their data. We made the mistake of asking for API access. They saw this as a red flag, investigated us, realised we were technical, and booted us off the platform. So we needed a replacement.

We decided to build it ourselves. We had all the needed components: data ingestion and map layers. It took about one developer-week to create the first version.

Why not release it? Allowing people to explore our data might:

- encourage inbound traffic;

- crowdsource the debugging and interrogation of our data for internal use;

- and help test the interface for a grid capacity discovery product, if we pursued that.

We launched the tool, called Scout, shortly before Christmas.

Scout did well, with a few hundred visitors, some acclaim on Twitter and LinkedIn, and emails and comments thanking us for it; it was our most-used product.

We’d like to think we caused a stressful Christmas at Landstack, who released Landstack Lite, a free version, in early February.

Learnings

Scout was our most-used product. Its users weren’t our target market, but some were. We had vague ambitions to use it as an inbound marketing tool, but we never capitalised on it. This was a missed opportunity.

There was some accidental product-market fit. We found an organic audience for our side project; making our data free and easy to access provided genuine value.

Tract Editor (December 2024 - March 2025)

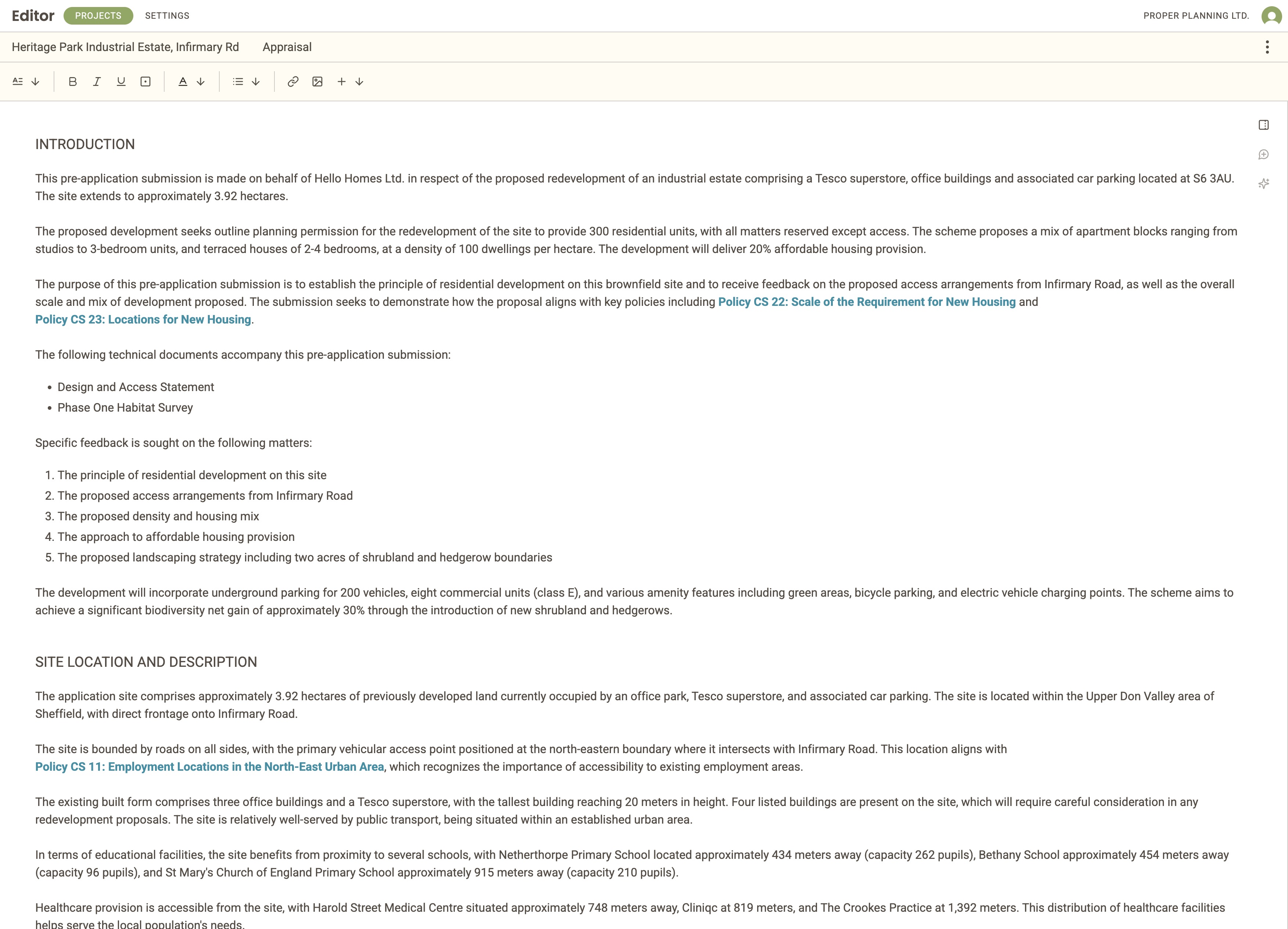

During the same tech sprint that produced Scout, we started considering reviving the planning applications platform.

We had all this information in our database – most required for the desk reports for planning applications – but were only using it for appraisals. To drive down the cost of planning applications, we needed to automate as much of the process as possible, including writing these reports.

Since we abandoned the idea of doing property development ourselves, we considered selling the tool directly. Many US startups help draft documents in development and construction, so there was some precedent.

A demo came together quickly. We dumped our appraisal output into a JSON blob. We parsed policies from an LPA's local plan. We built a document editor using open source components. We chained LLM prompts with our planning information – and got good results. A vision for this product began to form. We'd sell an LLM wrapper to planning consultants and developers to speed up document drafting. Then we'd expand to become the platform for managing all their projects, each with dozens of documents - hundreds with revisions. Hundreds of thousands of planning applications are submitted yearly, but no tool captures the institutional knowledge that compounds from project to project.

This felt promising. It played to our strengths as software developers. There was a sales playbook we could follow and our investors would understand for the next round. Preliminary discussions suggested the market was more open to our product: even planners realised they needed an answer to the AI question.

There was also a path to apply our technology to the US market, particularly California, which has its own housing crisis and legal hurdles.

We could build tools to help people navigate applications like lot subdivisions or rezoning petitions, or a tool for searching trial court rulings. Developers sometimes sue the city council, and these rulings don’t automatically become planning policy like Planning Inspectorate rulings in England, but they’re useful. Developers pay land use attorneys a lot of money to research them. Or we could help multijurisdictional landlords keep up with different regulations.

The common thread was our ability to ingest large numbers of documents, map their content onto a geospatial layer, and ask meaningful questions. Our technical foundation could support multiple business models in the UK and US.

Expanding internationally would require significant resources and market knowledge. We decided to focus on validating our core product with UK customers before pursuing US opportunities.

JRThis might have been another fatal error. Going straight after the US market and competing directly with SchemeFlow and friends would at least have cauterised the market sizing worries that eventually killed us. I have a sense that US construction (broadly understood) is a faster market, too, so we might have addressed some of the market quality issues too.

Setting up design partnerships

Towards the end of 2024, we set up calls with several planning consultants. We asked about their workflows and what tools. We described our vision and showed them our demo. The responses were all positive.

Narrowing focus to pre-app letters

After a month of calls and building, we realised our product was too general-purpose. We needed to focus on a specific problem. We had little evidence of selling this software and wanted a clear use-case to ground our offering.

We focused on pre-app statements. Most local authorities ask major developments to get pre-application advice: feedback on an initial proposal before submission, to ensure the basics are solid. It was the simplest document we saw. Most applications go through pre-app first – about 80%, according to one customer – it’s usually step one. We knew the costs and timelines, so we could anchor the pricing. And we had most of the information to generate them.

This led to a product called Tract Editor. Users would draw their site boundaries on a map, and we would pull existing site information. We could generate and reuse our appraisal output, so this was easy. We could pass this information into an LLM to produce a first-draft pre-app statement.

We’d add normal document editor features – comments, versioning, WYSIWYG, etc. – to integrate it into their workflow and avoid needing a perfect first draft. It could get you a reasonable starting point, like a junior planning consultant, which you could refine in a familiar environment.

We built a good tool that produced compelling first drafts from minimal information. It had a smart Q&A UI allowing the model to ask the user questions and regenerate sections based on the answers. It treated the planning system as a first-class citizen of the document editor, rather than focusing on the AI. It cited its sources and provided references for the quoted planning policy.

Our design partners seemed happy. We had made a marketing website and received good feedback from industry people. We chose a price of £99/user/month. We were ready to start selling.

Learnings

By this stage, we knew to talk to customers before, during, and after building a demo, and we didn’t spend too much time coding before getting positive feedback. What we did wrong was assume ‘positive feedback’ meant ‘desire to purchase’.

Customer switching costs have a psychological as well as economic logic. Better alone doesn’t mean people will use it. You’re competing with another workflow plus any status quo bias, which can be significant.

The Decision To Stop (March 2025)

When we offered a 50% discount to our design partners and asked what would get them to commit, their response was telling. Despite positive feedback, they wanted significant additional features like full planning statements before signing. This forced us to confront several hard truths:

- Despite positive feedback, customers weren't ready to commit, even with steep discounts.

- After nearly two years, we had zero revenue to show for our efforts. (We clearly weren’t great at this!)

- Our opportunity cost was rising as the tech landscape evolved rapidly.

- While we might build a business that could support us, we couldn't see a path to the venture-scale returns our investors deserved.

- The British market was too small, fragmented, and resistant to change for us to progress at the speed and scale our investors required.

Any one of these challenges could have been addressed. But collectively, they showed we faced months of struggling to secure small revenues through manual sales processes in a market with no clear path to venture-scale growth.

We considered pivoting to the US and drastically reducing our burn rate. Ultimately, we chose to return the remaining capital to our investors and walk away.

JRIn startup folklore, this would have been the character-building bit where we scrap everything and pivot to the US, to eventual glory. But I think I lacked the delusion needed to keep fighting.

Having made the decision to close the company, and having written this document, I now feel fairly confident that we could have made this work, somehow, in some form. This, I think, is proof that our basic analysis is correct: Tract died because we didn’t think seriously enough about building a business, because we didn’t focus aggressively enough on understanding what we were doing and learning from our mistakes.

Reflections

Things we did well

Fundraising

We raised capital for an unconventional business model in a challenging sector. In a difficult fundraising environment, we secured funding from institutional investors and angels who believed in our vision to transform the British housing market. This is no small feat for a pre-revenue company in an industry not known for technological innovation.

Technical Execution

We built good technology and solid products:

- Our data infrastructure effectively ingested and processed complex planning and geographic information.

- Scout became a useful tool with recurring users and positive feedback.

- Our Appraisals product was fast, well-designed, and provided useful information for its hundreds of users.

- Tract Editor produced high-quality planning document drafts that impressed industry professionals.

These products were built upon useful primitives that enabled quick experimentation.

Pivoting

When we recognised our land promotion strategy wasn’t working, we decided to pivot quickly. We parted ways with the non-technical employees not involved in building Tract Editor. We found design partners enthusiastic about our product and committed to giving us feedback, while keeping our investors informed about our strategic shift.

Closing Down

There are many ways in which we wasted time and money. But we are proud of the fact that we closed down the company because we couldn't see a way to make it work for our investors, and I think we can all sleep well knowing that we made the right call.

Learning and building relationships

We developed valuable relationships. From planning consultants to developers to land agents, we built a network that provided insights, feedback, and opportunities that would have been invaluable had the business continued.

We knew little about planning before this. But learned enough to build something that impressed the industry experts. This isn’t a complete win - we didn’t convert them to paying users. But they took us seriously. That’s not something we were certain we’d manage at the outset and gives us confidence moving forward.

Reasonable Errors

By 'reasonable', we mean mistakes that were understandable given the available information and our natural inclinations as founders.

Our technical and product execution was strong. Our ultimate challenges were market selection, business model fit, and the British planning system’s dynamics rather than our ability to build useful technology.

Overestimating the British market's size and receptiveness

The British proptech and planning market seemed substantial, given the dramatic land value increases from planning permission. There seemed to be a venture-scale opportunity, especially as several British proptech companies secured funding during our journey.

Building a venture-backed real-estate company

If our software could help many sites secure planning permission, it made sense to capture as much of that value as possible. But we underestimated the uniqueness of each site’s challenges and the “hand-cranking” needed to get landowners over the line. The way to run a business like this is to use off-the-shelf tools and raise money from institutions seeking a less risky 10 to 20% IRR.

Focusing on technology over business development

As technically-oriented founders, we gravitated toward building solutions. When faced with challenges, our impulse was to solve them with better technology rather than rethink our market approach. This technical optimism is common among founders with our background and was reinforced by the emergence of powerful new AI tools.

Building a team too early

Conventional startup wisdom encourages bringing on talent to accelerate growth. With funding secured and ambitious goals, adding team members seemed logical.

This is a classic startup dilemma: you need people to build and sell your product, but adding headcount increases burn rate and creates complexity before validating your revenue model. The error wasn't in hiring - many successful startups scaled their teams pre-revenue - but rather that we didn't have a clear hypothesis about how these hires would validate our core assumptions.

There's no perfect formula here. Too little hiring can mean missed opportunities and founder burnout; too much creates financial pressure and overhead. Our mistake was not ensuring each hire was tightly coupled to the critical path to revenue.

Not entering the US market

This might have offered more opportunities. Many VC-backed proptech companies founded before and during Tract’s lifetime (e.g. LandTech, SchemeFlow, PermitPortal) expanded to the US. Land use and zoning varies across US states, but traction in one may have been enough to raise the money to fund others.

But our challenge was understanding users deeply enough to build something they'd pay for. If we struggled in our home market with networks and cultural understanding, it's not obvious we'd have fared better in the US.

Unforced Errors

Not taking more advantage of Scout’s early success

We could have done more here to take advantage: collected more emails; added more datasets and features; been louder.

HDThe relevant period overlaps with Jamie’s paternity leave and is on me.

Not talking to landowners from the Attract prototype immediately

We had a chance to learn a lot about our key market months before we did, and we didn’t.

Not talking to land agents immediately

We assumed a big, slow, fractured market could be fixed without understanding why it was that way.

Time and money spent on non-essentials

These included an office, website and branding, a trip to America, contractors, and unnecessary employees. All of this was to appear to be running a startup – LARPing as founders – rather than building a business.

JRThis is the thing I’m most angry with myself about. It smacks of vanity and stupidity, and I should have held myself to a higher standard.

We also worked on side projects – including some open source work – that we wanted to exist but weren’t on the critical path to revenue.

Other possible factors

Cofounder fit

We get along well, but our skill sets aren’t especially complementary. There’s significant overlap, and we didn’t hire thoughtfully enough to correct that.

Energy levels

As mentioned in the ‘rising tides’ learning below, the past year has felt challenging, and neither of us feel that we have been our most productive or maintained the high energy and urgency needed to make progress.

Remote work vs. IRL

We started with a strict in-office policy, but this was disrupted by a remote hire, and we let it slip. This affected focus and morale.

JRThis one is on me. TBH, I made a mistake in choosing the office – it’s dark and cold and upsettingly far away from the sun – but Henry has been much more fastidious about going than I have.

Advice for founders

The more time I spend advising founders, the clearer it gets that 80% of my value is repeating "don't die, don't lie to yourself".

Get to America

The US is the largest and most dynamic market. Even niche industries are large enough for venture-scale companies to exist. This is rarer in Britain.

If your value proposition is built around saving labour costs or augmenting productivity, Britain’s lower median salaries are a ceiling on both the value you can create and the portion you can capture as a vendor.

Prioritise finding users in America if you want to raise money from American VCs. They will invest in European companies but heavily discount non-US revenue.

Choose your market wisely

Consider the market size, but also assess how receptive your target users are to new products and workflows. Questions to ask:

- Does the market have early adopters willing to try new solutions, or is it dominated by late majority/laggard customers who wait for proven technologies?

- Can you easily identify and access decision-makers? Markets with clear purchasing authority and shorter sales cycles allow faster iteration and learning.

- Do potential customers engage with product demos, respond promptly to communication, and provide actionable feedback?

- Are there self-contained pain points you can start selling a solution for, or a long tail of features customers need before they’ll pay?

- Is the customer base concentrated enough to build momentum through reference customers, or so diffuse that each sale requires starting from scratch?

Stay lean

We hired too soon, rented an office, and spent money on branding/design before having a clear revenue route. Money gives you more latitude, which means more opportunities to avoid necessary actions.

Be aggressively commercial

We focussed too much on building a theoretically sound business model and too little on testing it in the market. If we had asked “what have we learnt from users?” throughout 2024, it would have exposed that very little informing our product decisions came from conversations with our target market. Get traction with your target users before raising money.

We were distracted by Tract’s potential to help solve the housing crisis. But since we never made any money, we couldn’t keep going, making it irrelevant. It’s great to have a mission beyond making money. But if it doesn’t contribute to making your business sustainable, it will need to take a back seat for a few years.

The adage that ‘a rising tide lifts all boats’ is true, but incomplete. Success not only lifts you, but it changes you. It gives you more confidence, energy, and a faster learning rate. Conversely, treading water in a low-tide harms you. It saps your energy, forces you into strange epicycles. Beware treading water.

Test your hypotheses

We often learned something that showed us we had to change, but it took months to ask the right questions or perform the test. When considering an idea, think of ways to instantly find out if it’s flawed. For instance, it took too long to realise referring sites to developers through Attract wasn’t an easy way to get short-term revenue. We knew people who did referrals on the side and how the process worked but never drilled down into how long it took and what made the conversations drag on.

What's Next?

Jamie

I'm open to new projects, opportunities, jobs, or ideas.

I'm open to relocating to San Francisco.

My priority is to find truly excellent people working in a culture of high performance. Otherwise, I'm agnostic with respect to sector, stage, size or role.

My website is jamierumbelow.net. My Twitter is @jamierumbelow. You can email me at [email protected].

Henry

I'm spending the next few weeks writing and attending to life admin. I'm tempted by the thought of another startup while the lessons from the last one are fresh. I'm giving thought to ways I can be useful before committing to the next path. Some things I'm interested in:

- Buildings and urbanism. Similar to Tract's mission. I'm cautiously optimistic that we are going to increase the rate of building in the next few years in the places where it is most needed.

- I'm increasingly concerned by our shrinking industrial base. In Britain, I think high energy costs are a major factor. And in both Europe and America I'm worried about what we can rely on if relations with China worsen.

- AI. Obviously the biggest story this decade the area in which I have the most professional experience.

I'm open to relocating to the US.

You can view my website and socials at henrydashwood.com.

My email address is [email protected].

Appendices

Further Reading

Here are some resources for those interested in the problem space:

- The Housing Theory of Everything

- Foundations

- Small Builders, Big Burdens

- How Tech is Transforming Site Selection

General startup reading recommendations:

- What I’ve Learned From Users

- The Mom Test

- Entrepreneurship changed the way I think and How Terraform Navigated The Idea Maze

- Poor Charlie’s Almanack

- Staring into the abyss as a core life skill

Some pieces from Thesis Driven about alternative funding models to venture capital that better fit real estate plays:

- OpCo-PropCo Models and the Firms That Fund Them

- The Big List of OpCo-PropCo Investors

- The Future of the OpCo-PropCo Model

- Everything You Need to Know About Raising a PropCo

- Insights from Blueprint: OpCo-PropCo Models

- Three Emerging Models for PropCo "Seed" Investments

- Alpaca's Big PropCo Play

- Structuring Great OpCo-PropCo Partnerships

- The Biggest Structuring Mistakes Real Estate Entrepreneurs Make

- Solving the Challenges of OpCo-PropCo

- Five Ways New Real Estate Concepts Are Getting Funded Today

- 'PropTech' Needs to Die

- Who is Still Investing in Real Estate Tech?

- Who is Still Investing in Real Estate Tech? 1H 2024 Edition

- Thinking Like an Institutional Investor: Five Things You Need to Know

- Plotting a Sponsor’s Next Move

Things that should exist

- Appeals and planning apps search. The industry leader, COMPASS, is overpriced and pissing everybody off. Proper appeals and planning application search, including semantic search (“give me every planning application in this borough within the last decade that was rejected because of a disagreement about materials”) could be a nice product.

- An accurate grid capacity map and trading platform. See Interlude: The Grid above.

- Better industry-specific content. Most planning media is rubbish; an LLM could do just as good a job; thoughtful humans could do much better (who’s the Matt Levine of planning?).

- LLM-powered web scraping. Frameworks like scrapy and its long tail of ancillary services are valuable, but many use cases need more intelligence, which modern LLMs could provide.

- A tech-enabled land promoter. We still think somebody should do this – just not via VC funding – but there are ways to reduce planning application costs and make this business work.

Things that already exist

|

Name |

Countries |

Services |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

USA |

Land Info |

|

|

|

USA |

Land Trading |

|

|

|

UK |

Land Trading |

|

|

|

UK |

Grid Access |

|

|

|

UK |

Planning Appeals |

|

|

|

UK |

Appraisals |

|

|

|

USA |

Real Estate Info |

|

|

|

Australia, Canada, France, UK, USA |

Urban Planning |

|

|

|

UK |

Feasibility |

|

|

|

UK |

Land Trading |

|

|

|

UK |

Grid Access |

|

|

|

USA |

Feasibility, Land Info |

Full service architecture firm. Just in a few Texas cities atm |

|

|

USA |

Land Info, Real Estate Info |

|

|

|

UK |

Planning Appeals |

|

|

|

UK |

Planning Appeals |

|

|

|

UK, USA |

Grid Access |

|

|

|

Australia, France, UK, USA |

Real Estate Info |

|

|

|

USA |

Property Platform |

|

|

|

France, UK, USA |

Appraisals, Grid Access |

|

|

|

USA |

Cost Estimates |

|

|

|

Australia, Canada, France, UK, USA |

Urban Planning |

Formally Delve from Sidewalk Labs |

|

|

USA |

Cost Estimates |

|

|

|

USA |

Permitting Documents |

|

|

|

Canada |

Grid Access |

|

|

|

USA |

Codes, Land Info |

They charge $1,499 per report |

|

|

Australia, UK |

Land Info |

|

|

|

USA |

Real Estate Info |

|

|

|

USA |

Data Driven Developer |

Homebuilder helping clients navigate bureaucracy |

|

|

USA |

Planning Departments |

|

|

|

USA |

Grid Access |

|

|

|

USA |

Data Driven Developer |

|

|

|

France |

Land Info |

|

|

|

UK |

Land Info, Mapping |

|

|

|

UK |

Land Trading |

|

|

|

UK |

Land Info |

|

|

|

USA |

Land Info, Real Estate Info |

|

|

|

UK |

Land Info |

|

|

|

UK |

Land Info |

Try their new, free product, Landstack Lite |

|

|

USA |

Renderings |

|

|

|

USA |

Codes |

Nonprofit |

|

|

UK |

Land Info |

|

|

|

USA |

Grid Access |

|

|

|

USA |

Data Driven Developer |

|

|

|

USA |

Grid Access |

|

|

|

USA |

Grid Access |

|

|

|

UK, USA |

Appraisals, Codes, Land Info |

|

|

|

USA |

Permitting Documents |

|

|

|

USA |

Permitting Documents |

|

|

|

UK |

Land Info |

Made by Serac apparently |

|

|

USA |

Permitting Documents |

|

|

|

USA |

Real Estate Info |

|

|

|

USA |

Codes, Planning Committee Info |

|

|

|

UK |

Consultant, Grid Access |

|

|

|

UK, USA |

Permitting Documents |

|

|

|

UK |

Land Info |

|

|

|

UK |

Land Info |

|

|

|

USA |

Data Driven Developer |

|

|

|

USA |

Renderings |

|

|

|

USA |

Feasibility |

|

|

|

UK, USA |

Consultant, Grid Access |

They make http://ipsa-power.com/ |

|

|

USA |

Data Driven Developer |

|

|

|

UK |

Appraisals, Referrals |

|

|

|

USA |

Codes |

|

|

|

UK |

Real Estate Info |

AI-assisted valuation reports for chartered surveyors |

|

|

USA |

Land Info, Real Estate Info |

|

|

|

UK |

Land Info |

|

|

|

UK |

Real Estate Info |

|

|

|

UK |

Grid Access |

|

|

|

Australia, Canada, USA |

Codes, Land Info |

|